Nobody needs to be told about the impact that DVDs, and now Blu-Ray, have had on our home entertainment standards. It’s become all we know in regards to tangible home movie solutions, obliterating the VHS tape out of our lives and sending our VCRs to the bottoms of closets, basements, and landfills. No longer do we rewind, fast forward and waste time shuffling through miles of tape for crummy video quality. We jump, we skip, we zoom, we watch bonus features and we do it all in HD quality with Dolby Digital sound.

Though you may have hundreds of your favorite films kept on these fantastic shiny discs, do you really know how they function? It’s not just a piece of plastic. Do you know how they store their data, interact with your player and remote, and get images and sound to your TV and speakers? Many people are clueless about how a DVD disc and player actually works – they just know they should keep from abusing the shiny part, and shouldn’t use it as a coaster. While those things are very true, there’s a lot more to a DVD than sticking it in your player and waiting for the lion to roar. Let’s take a layman’s look at a DVD’s anatomy and how a DVD player reads it to craft the movie and sound stored within.

Consider an LP record. These records are vinyl discs with all sorts of bumps and grooves across their surface. The needle slides through the groove and feels the ups and downs in the record, which produce the sound you hear. This concept is similar for DVDs, but with advanced technology.

Similar to a vinyl record, a DVD stores its data in millions of little bumps in the layers of plastic that make up the disc. There are many layers that compose the DVD, and all the layers together form a fluid moving track of data that can be read by the player, which spirals from the center of the disc towards the outside. (If you’ve ever seen a writable disc where the outer part is a different color than the rest, that’s because the DVD hasn’t been written all the way to the end, and isn’t entirely filled to capacity). Though DVDs appear smooth and solid, they have tracks much like LPs, and these tracks house these bumps. There are miles of bumps on a single DVD. Instead of using a needle to read them (yikes!), DVD players use a laser. The outside of a disc covered in a thin coating to protect the grooves, all the layers are compressed together and the disc is made. One side of a DVD is usually non-readable, and it is where the label goes. Some discs, however, can be read on both sides.

DVDs are also not entirely plastic. In their core is a thin sheet of aluminum used for reflection purposes. It helps the laser read the DVD. Light is shined through the plastic disc, which is reflected to a lens on the opposite side. The lens is what catches the laser, and as the laser reads the disc, it shines differently through the pattern of bumps in the plastic – which the lens interprets as film data by detecting the variations in the light. The laser is super thin and precise, which allows it to get down into the microscopic tracks and read those insanely tiny bumps.

Scratches or blemishes on your disc can cause the disc to not work properly because the laser cannot accurately read the bumps. But, while many people think it is dangerous to touch the readable side of a DVD, it is equally if not more dangerous to scratch the label side. This is because the data is written into the disc deeper than the surface of the readable side, and is actually closer to the label side than the side that gets read.

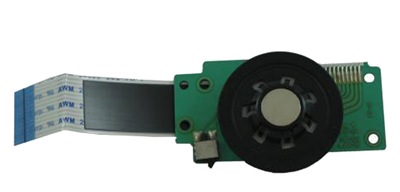

Obviously, all of the laser reading of bumps happens because your DVD player has a motor. If the DVD just sat still in there, not a lot would happen – the laser would be stuck reading the same place on the disc. So, the motor in the player spins the disc very fast, allowing the laser to move in a spiral form along the disc’s tracks and send the data to the DVD player’s computer for processing. The speed at which the motor rotates the DVD depends on the track being read. Tracks closer to the middle of the disc require it to be spinning faster, while the ones nearer the outside require a slower rotation.

This is where your DVD player’s computer comes into play, translating the laser’s bump readings into what you want to see and hear. DVDs are encoded in a format called MPEG-2, which is a digital compression format which allows the movie and sound to fit on the disc initially. A movie would never fit onto a disc of any kind without compression. The bumps on the disc represent the film’s data, and the MPEG-2 decoder within the DVD player translates this data into audio and digital signals. These signals then make their way to your TV via various cables and turn into audio and sound, just as any picture reaches your television and speakers. There is a lot of computer technology inside that makes all that happen, forming data blocks and sending the data to its appropriate places. While the outside of every DVD player looks vastly different, the insides all contain familiar components.

Reading light patterns and decoding compression is not all your DVD player can do. As you know, there is more than just a movie on that DVD. There are menus, special features, navigation, and all sorts of other functions. A tracking system within the DVD player moves the laser around to different spots on the disc so that it reads what you tell it to. When you navigate a menu, each part of the menu has a space on the disc that the laser jumps to. Same with skipping scenes while watching the film. This tracking mechanism is also what keeps everything in sync when watching a film, ensuring the laser stays in line with the data it’s supposed to be reading. The tracking system is the real heart of what the DVD player does. If it’s off, nothing works, so the fundamental purpose of the entire player is for the tracking system to keep everything in line.

Conclusion:

The DVD is a pretty complex object made up of a lot more than the eye can see. Fortunately, the DVD player knows how to navigate the disc and get your movie to the screen. Despite its complexity, the concept is really quite simple – data is stored in bumps, a laser reads them and a computer turns the readings into usable data. It really is built on the same principle as an LP, but takes that Flintstones technology a Jetsons world.

So next time you put a DVD in and prepare to watch Gigli, consider the fact that in your hand is a seven and a half mile long track of bumps that a beam of light is about to convert into a movie with the help of a computer. If you are actually holding Gigli on DVD, feel free to crack the disc in half and get a closer look at the layers and composition of the product. Then you can tell your pals that if you had just 3,333 standard DVDs, the data tracks on them, if laid in a linear path, would wrap completely around the earth.

3 comments for “How Stuff Works: DVDs and DVD Players”